Between scandal and success: TCD meets ‘Berlusconi: Condemned to Win’ Director Sam Blair

“The difference between madness and success is genius,” reflects Carlo Pellegatti, the voice of AC Milan for over three decades.

It is a line Silvio Berlusconi walked better than most. Certainly more brazenly than most.

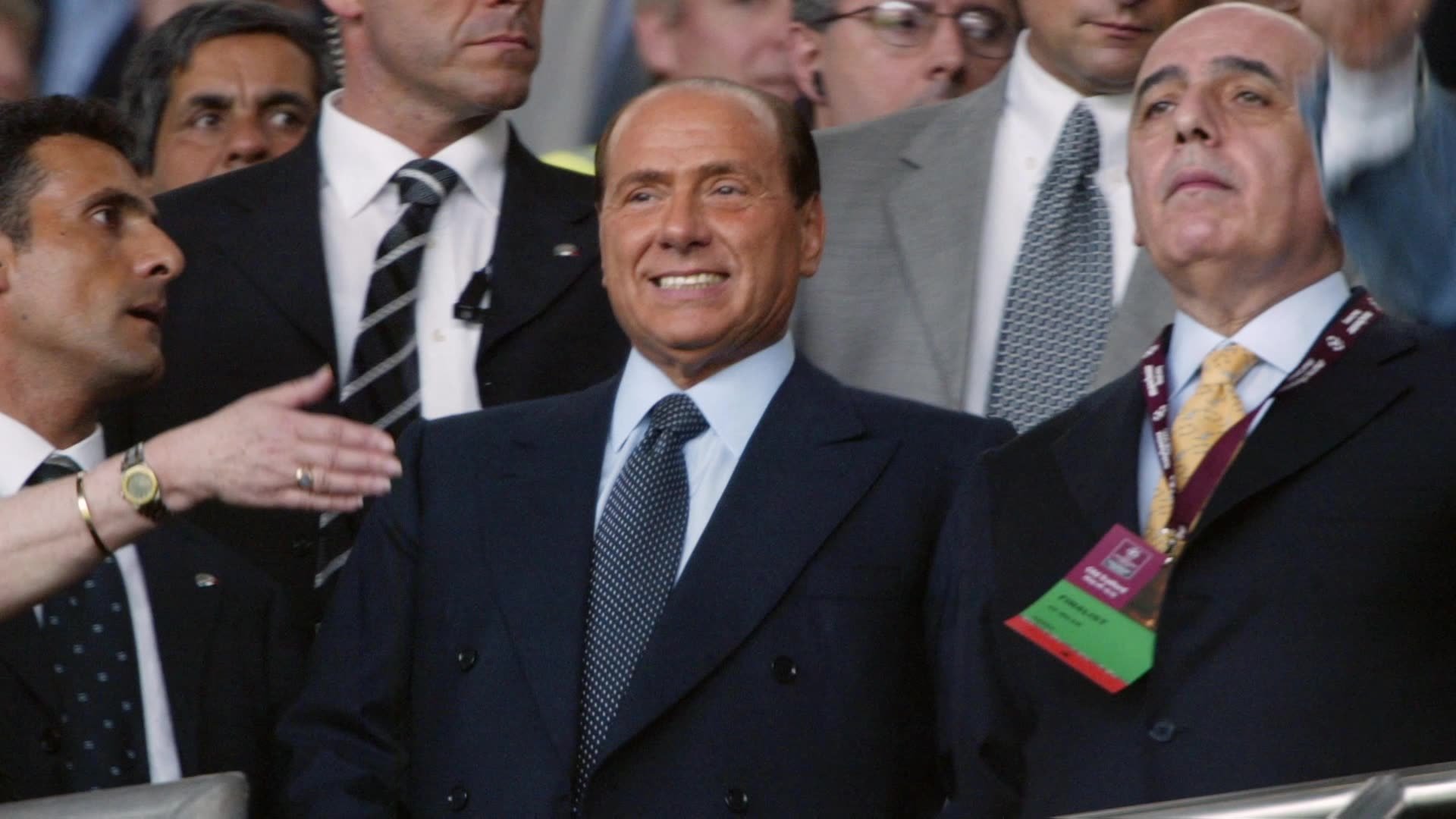

Two years on from his death, Berlusconi’s legacy remains complex and laden with caveats.

The man who through brilliant ingenuity and political help revolutionised television in Italy is also the man who repeatedly attacked the country’s judiciary.

The four-time prime minister who used his powers for ad-personam laws was also one of football’s great modernisers.

When it comes to Berlusconi, there’s a ying for every yang.

All images courtesy of ESPN.

In Sam Blair’s Berlusconi: Condemned to Win documentary, Pellegatti describes the late Milan president as a “visionary”.

Adriano Galliani, who spent three decades as the Rossoneri CEO under Berlusconi praises him as a man who changed football.

Former Milan managers Carlo Ancelotti, Arrigo Sacchi and Fabio Capello, cast the late Italian PM as a “loyal, sincere and intelligent man.”

But as historians John Foot, Alexander Stille and Ruth Ben-Ghiat suggest, there was a much darker side to Berlusconi.

His Murdoch-esque control of the media allowed him to dictate a political agenda that has paved the way for the populist rhetoric that has dominated the discourse over the past decade.

And yet, it is nigh-on impossible to separate Berlusconi’s sporting and political legacies, which is arguably what he had always intended.

It is also what Blair found so fascinating about the late Milan president.

“I'm not any more interested in sport than any average person,” he says.

“It's not the reason I want to make films.

“But sport has emerged as a kind of really powerful way to explore other things in the world. I mean, it reveals so much about the culture and society we live in.

“And I think this is obviously a story that felt like the ultimate sports story. In order to understand this relationship between power and politics, the way Berlusconi harnessed football and then football became a platform for him.

“That combination and that relationship felt so interesting to explore.”

If distinguishing between Berlusconi the media tycoon, Berlusconi the club owner and Berlusconi the politician is a complicated exercise that is not by chance.

The former Milan supremo was not one for compartmentalisation. As he quips in archive footage in the documentary, “conflict of interests do not interest me”.

And if his business success allowed Berlusconi to purchase Milan in 1986, then football proved to be an ideal launchpad onto wider and bigger ambitions.

“That was the strength of the documentary,” Blair says.

“Football and politics were deeply intertwined, especially with the creation of Forza Italia and Milan's success.

“It shows how football success was used as a political tool.”

Long before the words sportswashing entered the football lexicon, the beautiful game was the bedrock to Berlusconi’s political ambitions.

The name of his party, Forza Italia - Come on Italy - and him describing his arrival into the political arena as “entering the pitch” were both football references. Deliberately so.

To millions of voters, this was a football man using football language in a football-mad country.

When Berlusconi purchased Milan in 1986, the Rossoneri were nine years removed from their last Scudetto and had been relegated to Serie B twice in the previous years.

By the time he sold the club three decades later, Milan had won 28 major trophies under his presidency, including eight Serie A titles and five European Cups/Champions Leagues.

No wonder then, that voters in the archival footage in the documentary are convinced “he can do for Italy what he did for Milan.”

That faith would largely hold for two decades.

And yet, for all his flamboyancy, Berlusconi was the same man who before entering the political sphere was involved in the Mani Pulite investigation, modern Italy’s biggest trial, which effectively decapitated its entire political class.

That included Bettino Craxi, who had facilitated Berlusconi’s media success, before fleeing the country in the wake of the Mani Pulite trial, which led to the collapse of what is now known as Italy’s First Republic.

Despite his ties to Craxi, barely two years later Berlusconi stepped into the political arena, presenting himself as the outsider with no connection to the previous administration, who could run the country like a business.

Better still, like a successful football club.

“I think one of the key pieces of archival footage was this chat show in 1994, when he launched Forza Italia, and they started discussing whether Berlusconi was going to work as a politician,” says Blair.

“And this extraordinary debate happens where people are saying he can bring the success of AC Milan to Italy as a country. And that was like a proof of concept in a way that debate around sporting success was being completely translated into the idea of a political movement.

“The narrative was shifting from one reality to another.”

Nowhere is the crossover between football and politics more striking in the documentary than through archival footage of the 1994 Champions League final.

As Milan took on Barcelona in Athens, Berlusconi’s first government faced a crucial vote of confidence.

It led to the surreal sight of live updates over the vote being provided in the corner of the screen during the game’s broadcast on Rai 1 channel. For Berlusconi, football and politics were now one and the same.

And while the Rossoneri put Johan Cruyff’s “Dream Team” to the sword to triumph 4-0 in a match best remembered for Dejan Savicevic’s outrageous chip, Berlusconi survived the vote by 159 to 153.

The three-part documentary is Blair’s latest contribution to ESPN’s “30 for 30” series, which also features his movie on Diego Armando Maradona at the 1986 World Cup.

Blair has also directed documentaries on Steven Gerrard and snooker great Ronnie O’ Sullivan, yet Berlusconi presented a whole different and in many ways unique challenge.

“It was different because Berlusconi is not a genius athlete but a complex political figure,” he explains.

“I think I was then more interested in the way in which the people who we interviewed to tell the story were dealing with their conflicts around him.

“Berlusconi just remains this distant figure, who controlled the narrative.

“He had so much control over the way that his story was told because he owned the media. We tried to get an interview with him and we actually were getting close, but his health ended up ultimately making that impossible.

“But we tried to get as close as we could and explore how people that kind of push and pull of attraction and repulsion existed in people. And I think amongst the football fans, in some ways that was clearest.”

Football, again playing the role of the great equaliser.

“We interviewed Andrea Scanzi, a prominent Italian left-wing journalist who's a huge Milan fan,” Blair continues.

“And for him, the seductive power of this team that Berlusconi had assembled was always in conflict with his politics.

“And I think I was really interested in this seductive power that Berlusconi had over people.

“I was young at the time, but I was aware of AC Milan as this kind of untouchable footballing machine that was powerful and beautiful at the same time. And that's an incredibly powerful thing.

“I suppose I was interested in how that seduction plays out in our world now.”

Blair brings that question to life in his movie, which premiered in September and charts Berlusconi’s rise from a media tycoon to Italy’s four-time Prime Minister.

Rather surprisingly, for a documentary about a media tycoon, sourcing footage proved to be a major stumbling block as most Italian archive material is owned by Mediaset, Berlusconi’s former company, which does not license it.

That left Blair and his team having to rely on archival footage of people reporting on Berlusconi from the outside. That, in turn, posed the risk of a subtle but crucial shift in perception.

“It was a real challenge, we had to try and walk a line,” he says.

“I don't think it's a good idea just to be dogmatic in storytelling. You want to create a tension that the audience is navigating between.

“But a lot of it [archive material] was this sense of shock from the outside world looking in at what was happening in Italy. And that's very dramatic to show, but we didn't just want all this criticism of Berlusconi.

“We kind of wanted to understand on the inside how his message was so seductive.”

The process is helped by interviews with some of Berlusconi’s closest allies and confidantes such as Fedele Confalonieri, head of his Mediaset empire, and Vittorio Dotti, who served as his lawyer from 1980 to 1996.

It is the latter who reveals his client was initially reluctant to buy a football club.

“My fortuneteller told me that buying Milan would bring me bad luck,” Dotti recalls Berlusconi saying, explaining he had initially set his sights on Inter Milan.

How different history would be had he followed his instinct.

Confalonieri, meanwhile, is unexpectedly candid about his friend’s political demise, much to Blair’s surprise.

“I was expecting it to be harder to get him to wade into some of the grey areas of Berlusconi and his life, but he kind of owned them in a way that I was really pleased about,” he says.

Galliani, Ancelotti, Capello and Sacchi dominate the conversation from a football standpoint, but predictably skirt around political issues.

“I think it's a kind of very touchy subject and I think for footballers and managers to wade into that space where they kind of have to put their political opinions on the line,” says Blair.

But former Milan midfielder Zvonimir Boban, who Blair describes as an “incredibly astute, smart man” bucks the trend decisively.

“Boban was one of the most pleasurable interviews because he kind of traverses the issue,” he says.

“Here you have this incredibly smart, astute, educated man who could grapple with the problem inherent in the Berlusconi conflict.”

Yet arguably the most striking interviewee in the documentary is Paolo Tarozzi, whose own experience of Berlusconi is extremely personal.

In the opening episode, Tarozzi appears as a die-hard Milan fan, before being offered the position of Rossoneri press officer.

From a Berlusconi believer, Tarozzi, whose dramatic delivery is explained by his past as amateur theatre actor, finds himself as part of the Berlusconi empire.

By the final episode, he too has come to confront the troubling legacy of the former Milan president.

“He was really someone who found himself in total conflict with this awe he felt of Berlusconi but then the reality that gradually dawned on him of what was behind the facade,” explains Blair.

Has Blair’s own opinion of Berlusconi changed while filming the documentary?

“Yes, I think it did. You know, in fact, it really changed,” he reflects.

“It was a big education for me. And I think, again, my understanding of Berlusconi was shaped by the way that we in the UK in particular used to look at Italy and Italian politics as this kind of crazy circus that's going on.

“I relate him in my imagination to a show on British TV called Euro Trash. It was all about these kinds of crazy characters in Europe doing crazy stuff. You know, you could be a bit sexy and a bit over-the-top and he [Berlusconi] seemed part of that world.”

But as Britain experienced its own descent into populism, characters like Berlusconi suddenly seemed to be far closer to home.

“This country caught up with Italy in terms of the way politics went completely mad,” he says with a wry smile.

“You know, the way Brexit turned this country upside down, the political narrative shifted and populism emerged as a force here.

“And suddenly, it seemed like understanding someone like Berlusconi would be helpful to understand what was going on in Britain.

“It felt like Berlusconi in some ways is ahead of the curve as a character.

“And for me, it was a big education. I think there's a tendency to knee-jerkly look at someone like Berlusconi and treat them like a kind of joke or as this kind of extreme case.”

Italy’s longest-serving Prime Minister, Berlusconi arguably dominated Italy’s political scene like no other man bar perhaps Giulio Andreotti post World War II.

Yet even a man of his powers was ultimately brought down by a series of scandals, including a four-year sentence for tax fraud and being convicted of paying a juvenile sex worker and then misusing his official position to try to cover up their relationship - he was acquitted of both charges on appeal and did not serve time in prison for tax fraud.

Berlusconi sold Milan in 2017, with the Rossoneri winning a first Scudetto in over a decade five years later, just months before his party returned to power as part of a conservative alliance.

By then, however, he was a largely peripheral figure in a country that had danced to his tune for the previous three decades and was not named prime minister.

A profoundly ironic final act for a man so obsessed with narratives.

Berlusconi: Condemned to Win is available to stream in the UK on ESPN+, Apple TV, and available for purchase on YouTube.

Dan Cancian is a writer and journalist for Forbes, Destination Calcio and others. You can find more of his work on X.